![]()

)

)

The Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization: Managing the First Global Burglar Alarm

By John Mathiason

The Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty was designed to further elimination of weapons of mass destruction by assuring all parties that no one will be able to test nuclear weapons without everyone else knowing it, thus discouraging testing and therefore the development of the weapons themselves. When the United States Senate rejected the treaty, one of the formal reasons -- probably not a real reason -- for doing so was that the technology involved and the organization created to use it were not capable of detecting tests. The paper examines whether the CTBTO, as currently managed, is able to carry out its tasks. In terms of what is asked of it, the CTBTO has been given a task that is far beyond the usual limits of international organizations and this places a larger-than-usual burden on the management of the organization. The experience of the CTBTO to date illustrates both the potential and some of the limitations of international organizations taking on significant trans-national regulatory functions. The conclusion of the analysis is that the CTBT, when it comes into force, will be able to verify compliance and that this should not be a ground for any State to refuse ratification.

The Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) has been characterized by the staff of the Provisional Technical Secretariat of its Preparatory Commission as "the first global burglar alarm".[1] The treaty was designed to assist in the elimination of weapons of mass destruction by making it impossible for any State to undertake tests of nuclear weapons without being detected. It was based on the premise that all States would undertake never again to test these weapons and that a regime would be established that would guarantee that the commitment was kept.

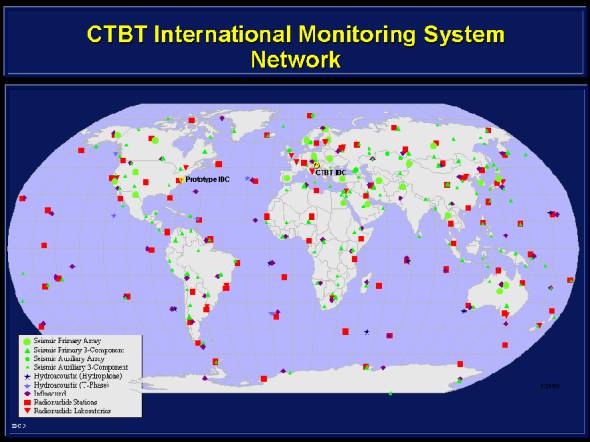

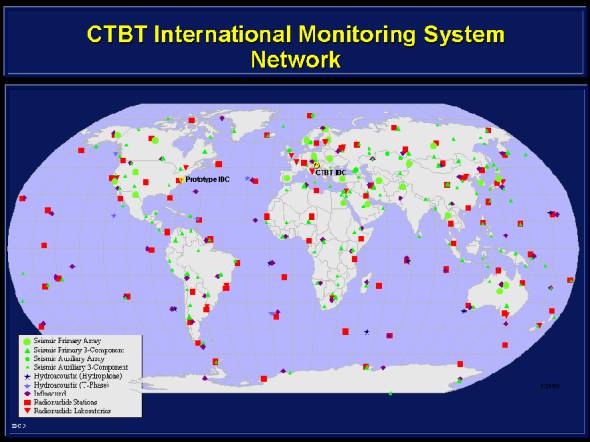

Under the treaty that guarantee would be provided by the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization, an international organization which would manage a network of seismic and radio nuclide detecting stations linked by a satellite communications system. The system would be able to detect any explosion above a particular magnitude, pinpoint it and permit a plausible analysis of its type. At that point, an inspection process could be requested with on-the-ground inspectors verifying the type of explosion.

The underlying premise of the system is that, since no test could go undetected and since, without testing, nuclear weapons would not be credible, incentives to develop and maintain them would disappear and this would facilitate the larger process of nuclear disarmament.

The verification system to be set up under the treaty is one of a new breed of international organizations, which have attributes beyond sovereignty. States in which the seismic stations are located do not control the stations, nor can they interfere with the transmission of signals. They are not asked to acquiesce to any reporting by the CTBTO, although they can refuse to accept inspections (at their peril from the other States Parties).

The treaty was opened for signature on September 24, 1996 and will enter into force when 44 States, including several that must do so, have signed and ratified the Convention. As of today, 41 of the necessary 45 have signed, but only 30 of the 44 have ratified. The most prominent non-ratifier is the United States, although it has signed the Convention. In 2000, the United States Senate voted against ratification by a vote of 48 in favor to 51 opposed. The basis for the rejection may have had mostly to do with domestic politics, since the vote was almost entirely along party lines, but given as a reason for rejection was a belief that the treaty was unverifiable. As Senator Warner of Virginia stated after the vote:

Of particular concern was the zero-yield threshold. Legitimate concerns were raised about our ability to monitor violations down to the zero-yield level, and with our need to conduct, at some point in the future, very low yield nuclear explosions to verify the safety of our stockpile, or to ensure the validity of the stockpile stewardship program. Perhaps it would have been better to agree to a Treaty which allowed very low yield testing -- as all past Presidents, beginning with President Eisenhower, have proposed. [2]

Implicitly this meant that the organization established to verify the treaty would not be able to manage its task successfully. If that were to be the case, the treaty would be fatally flawed. Whether the organization can be managed successfully is therefore a significant question.

Article IV (Verification) of the Treaty and the Protocol establish the verification regime. Such a regime - consisting of IMS, IDC, consultation and clarification, on-site inspections and confidence-building measures - "shall be capable of meeting the verification requirements of the Treaty" at its entry into force. In other words, the main elements of the verification regime have to be prepared in advance. This was presumably because when the treaty was agreed, it was correctly assumed that the ratification process would be slow.

The verification regime consists of five parts, as described in the PTS summary of the Treaty.[3]

International Monitoring System. The purpose of IMS is to detect and identify nuclear explosions prohibited under article I. As set out in annex 1 to the Protocol, IMS will consist of 50 primary and 120 auxiliary seismological stations equipped to detect seismic activity and distinguish between natural events - such as earthquakes - and nuclear explosions. It will also include 80 radionuclide stations - 40 of them capable of detecting noble gases - designed to identify radioactive particles released during a nuclear explosion. The radionuclide stations will be supported by 16 laboratories. In addition, 60 infrasound and 11 hydroacoustic stations will be designed to pick up the sound of a nuclear explosion in the atmosphere or under water, respectively.

International Date Centre. The monitoring stations will transmit data to the International Data Centre (IDC) at Vienna. As set out in part I of the Protocol, IDC will produce integrated lists of all signals detected by IMS, as well as standard event lists and bulletins, and screened event bulletins that filter out events that appear to be of a non-nuclear nature. Both raw and processed information will be available to all States parties.

Consultation and clarification. The consultation and clarification component of the verification regime encourages States parties to attempt to resolve, either among themselves or through the Organization, ambiguous events before requesting an on-site inspection. A State party must provide clarification of an ambiguous event within 48 hours of receiving such a request from another State party or the Executive Council.

On-site inspection. If the matter cannot be resolved through consultation and clarification, each State party can request an on-site inspection. The procedures for on-site inspections, which “shall be carried out in the area where the event that triggered the on-site inspection request occurred” are established in part II of the Protocol.

Confidence-building measures. To reduce the likelihood that verification data may be misinterpreted, each State party will voluntarily notify the Technical Secretariat of any single chemical explosion using 300 tonnes or more of TNT-equivalent blasting material on its territory. In order to calibrate the stations of IMS, each State party may liaise with the Technical Secretariat in carrying out chemical calibration explosions or providing information on chemical explosions planned for other purposes.

The last three of these elements can only be put in place before entry-into-force in the sense of having trained personnel ready to undertake the functions, although the calibration exercises under confidence-building measures can be done in the pre-ratification period.

The heart of the verification regime is the complex network of stations whose purpose is to detect evidence of any clandestine explosion. The network is a combination of different types of measuring devices. While these will be located in sovereign territory of Member States, owned and operated by those States, they will be, in the words of the Treaty "under the authority of the Technical Secretariat." The costs of establishing or upgrading the stations will also be borne by the CTBTO.

To run establish and run these stations, the TS will have to exercise quality control and ensure maintenance, even though formally the ownership and staffing of the centers will be a national responsibility. This means that the siting, equipping and calibrating the sites, as well as the construction of facilities, will have to be done by the TS. It will also have to oversee the training of the national staff that will act as custodians of the equipment.

The treaty calls for 337 monitoring facilities, including 321 stations and 16 radionuclide laboratories spaced around the world. (See map). The location of the sites was carefully negotiated and specified in an Annex to the treaty. Taken together, once operational, the stations could detect an explosion of less than 1 kiloton anywhere on the planet. Some say that the system could detect a building being destroyed by dynamite. The technology is designed to distinguish between natural events (tremors or earthquakes) and man-made events.

The largest number of stations (112) is located in the five declared nuclear powers. The remainder are located elsewhere, most in developing countries. Most of this remainder will have to be built. In his report to the 12th session of the Preparatory Commission, the Executive Secretary of the Temporary Secretariat reported that[4]

2. Since the reporting of activities to the Eleventh Session of the Preparatory Commission, the commissioning of the International Monitoring System (IMS) has continued at a steady pace. As of 26 June 2000, legal arrangements in the form of facility agreements or arrangements, or exchanges of letters, had been concluded with 64 States to regulate the activities of the Commission at 274 monitoring facilities, 60% of site surveys were complete and ready for installation work, and approximately 20% of stations were installed and sending data to the International Data Centre (IDC).

![]()

)

)

The treaty specifies that the monitoring stations will be linked by a satellite communications network that will function automatically. Data acquired by the instruments in the stations will be transmitted directly to the CTBTO headquarters in Vienna for analysis.

It is this feature of the monitoring system that is most innovative. No other verification mechanism has this automaticity. The transmission of data is completely outside the hands of national authorities. The only exception would be if the equipment were not to be working. This, however, would be taken as a sign that something was afoot and, in the event there was an explosion, other monitors would detect it.

Ensuring that the stations’ ability to transmit information is unimpaired will be a major concern of the TS over time. There is a five phase plan to install, test and operate the necessary connections via the satellite-based Global Communications Infrastructure (GCI) that is, according to the report of the Executive Secretary to the most recent Preparatory Commission, on schedule. As the report states:[5]

41. Twenty-three GCI site surveys have been conducted this year, bringing the total number of completed surveys to 80. Most of the installed very small aperture terminals (VSATs) as well as terrestrial lines to independent subnetworks are now carrying data to the IDC. As of June, six additional VSATs had been installed and 51 additional VSAT sites were at various stages of preparation. Licensing of VSATs is becoming the most significant obstacle to VSAT installation. An additional GCI hub is being installed in the USA and should be operational soon. The PTS and the GCI contractor, HOT Telecommunications Ltd, completed in May the fourth amendment of the GCI contract. This provides for an expanded roll-out period instead of the original three year period. This improvement will provide the flexibility to comply with the schedule of IMS site availability. In addition, a change order was completed to install routers at IMS and NDC sites, addressing the networking and security issues in connecting these sites to the GCI.

The central instrument for collecting, analyzing and disseminating data, the International Data Centre itself was developed in prototype before the negotiation of the treaty was completed and has, in effect, been transferred to Vienna. Many of the staff members of the prototype center have joined the TS. The main problems in installing the system, for which existing technology is adequate, is

Finally, in the event of an explosion (or allegations that one has taken place), the TS will be expected to field qualified teams of inspectors to verify. To be credible, these inspection teams will have to be known as technically competent, will have to be geographically balanced and will need skills in negotiation and conflict resolution in order to ensure access. This element of the system, the On-Site Inspection Program (OSI) can only begin to work once the treaty is in force and is the last that will have to be put into place.

During the preparatory period, the focus has been on reaching agreements on the technical methodology to be employed in inspections, on the training of potential inspectors and in simulating what would happen if it were to be necessary to undertake inspections. Because of the political ramifications, the development of an operations manual that would guide inspections has required negotiation. As the report of the Executive Secretary states:

43. The essential work of the PTS in the on-site inspection (OSI) area has centred around the development of the Operational Manual, OSI equipment procurement, and conduct of OSI training and tabletop exercises, with the broad goal of continued elaboration of the design of an OSI regime.

The design of the verification system appears to be adequate for the task, assuming that its elements can be completed. It will only work, and be credible, if the Technical Secretariat is able to do its work successfully.

There is a dilemma here. Until the Treaty comes into force, the secretariat charged with implementing it is temporary. This means that the management tasks are compounded by difficulties in planning (the date of entry-into-force cannot be assured), staffing (staff of a temporary organization cannot be given long-term contracts or career prospects) and finance (a temporary organization cannot make longer-term assessments).

The next question is, if the basic design was adequate for the task, whether the management of the international organization concerned is adequate. Here we are dealing with a somewhat complex situation. Until the Convention actually comes into force, the implementing organization is by definition temporary. This has implications for program planning, for personnel management and for financing.

For the managers of the TS, planning is crucial, because the Treaty specifies that the International Monitoring System should be in place when the Treaty comes into force, but the managers cannot say, with any certainty, when entry-into-force will occur. Indeed, in order to convince some States to ratify the Treaty, it may be necessary to have the system in place and demonstrably working.

The management response regarding the monitoring stations was reported to the Preparatory Commission at its 12th session in August 2000:[6]

21. The PTS is

developing an action plan in order to guide implementation actions in preparation

for an early date of entry into force of the Treaty. The action plan will

address issues such as: the development and implementation of management tools;

expanded use of procurement call-off contracts; the implementation of difficult

stations (such as, in Antarctica, high latitude stations, or isolated and

logistically challenging stations); operation and maintenance; means to

expedite the conclusion of “exchange of letters” or facility agreements;

and the optimum prioritization of implementation efforts for IMS stations.

By the end of 2000, according to its approved budget, the TS was expected to have a staff of 269 persons, of which 169 were graded as professionals. Table 1 shows the distribution of posts among main programs. According to the oral report of the Executive Secretary, as of 22 August 2000, the PTS comprises 238 staff members from 68 countries, and the percentage of women in the Professional category had reached 26.39%.[7]

|

Table

1. Staffing by program, 2000 |

|||||

|

Program |

Professional |

General Service |

TOTAL |

Percentage |

|

|

1. International Monitoring System |

33 |

19 |

52 |

19.3% |

|

|

2. International Data Centre |

70 |

24 |

94 |

34.9% |

|

|

3. Communications |

6 |

2 |

8 |

3.0% |

|

|

4. On-site Inspection |

12 |

4 |

16 |

5.9% |

|

|

5. Evaluation |

4 |

1 |

5 |

1.9% |

|

|

7. Administration, Coordination and Support |

44 |

50 |

94 |

34.9% |

|

|

TOTAL |

169 |

100 |

269 |

100.0% |

|

The relative priorities of programs can be seen from the staffing pattern. The largest proportions are in the International Data Centre (including communications, which is concerned with the analysis and dissemination of data), and in administration. This latter proportion is not really overhead, since the largest part of this is devoted to functions that are essential to the creation of the regime, including servicing of a large number of meetings in which PTS recommendations are reviewed, negotiating legal arrangements with States in which stations are to be located, and complex procurement. Table 2 shows the distribution of administration, coordination and support posts among functions:

|

Table 2. Distribution of Administration,

Coordination and Support Posts by Service |

||||

|

Service |

Professional |

General

Service |

Total |

Percentage |

|

Office of the Executive Secretary and Offices of the Directors |

6 |

6 |

12 |

12.8% |

|

O.2.Internal Audit |

2 |

1 |

3 |

3.2% |

|

P.1.General Services |

2 |

6 |

8 |

8.5% |

|

P.2.Conference Services |

7 |

9 |

16 |

17.0% |

|

P.3.Financial Services |

5 |

9 |

14 |

14.9% |

|

P.4. Personnel Services |

3 |

8 |

11 |

11.7% |

|

P.5.Procurement Services |

6 |

3 |

9 |

9.6% |

|

Q.1.Legal Services |

5 |

2 |

7 |

7.4% |

|

Q.2.External Relations |

4 |

2 |

6 |

6.4% |

|

Q.3.Public Information |

2 |

3 |

5 |

5.3% |

|

Q.4. International Cooperation |

2 |

1 |

3 |

3.2% |

|

Total |

44 |

50 |

94 |

100.0% |

When the PTS was established, the Member States were concerned with maintaining costs low. Two policies were enacted that have consequences for the long-term ability of the Secretariat to perform its functions. First, staff were given grade levels that were essentially lower than those that would have been given in a comparable international organization. The highest grade for directors is the Principal Officer (D-1) grade. Here, the model was the IAEA, which initially appoints directors at that level, but allows for promotion to the Director (D-2) level. Second, a strict rotation policy was put into place: after an initial appointment of three years, extension was possible for an additional two years and exceptionally for a further two years (for a maximum of seven years). Here, the initial policy of the IAEA was followed. The IAEA, however, had learned early in its history that certain functions required career staff and about a third of Agency professional staff have long-term contracts.

Most of the initial staff of the PTS did not have extensive experience with international organizations and there has been a learning period. However, it seems as though they are acculturating themselves to the constraints of working in the international public service.

The premise has been that turnover is good, because it allows for new staff with new knowledge to be recruited. However, like the Safeguards Department in the IAEA, the staff working in the technical programs of the CTBTO have no outside competitor. There is no other organization that will be performing its functions and, in effect, it will have to train its own staff. It is not an accident that the highest proportion of long-term contracts in the IAEA is in the Safeguards Department.

It is also becoming difficult to recruit qualified candidates because of the uncertainty of tenure. More importantly, the issue of who will be extended, for how long and with what performance criteria is becoming a staff-management issue.

The most dangerous aspect of the policy is that, based on a current estimate of entry-into-force is that it is unlikely to happen before 2005, almost all of the staff will have completed their maximum tenure and would be expected to leave just as they were most needed.

For PTS management, these problems cannot really be solved as long at the CTBT is a temporary organization. Still, the time may have come to consider the longer-term policy issues regarding human resources. The important issue is how to recruit and maintain the qualified staff necessary to build the verification system and then run it through the beginning years of entry-into-force.

The financing of the operations of the PTS is through a complex system of assessments of the States Signatories. The system is essentially a combination of “ability to pay” and interest, in that the bulk of the assessment goes to the declared nuclear powers who are signatories, with the United States contributing the largest share.

9. The

costs of the activities of the Organization shall be met annually by the States

Parties in accordance with the United Nations scale of assessments adjusted to

take into account differences in membership between the United Nations and the

Organization.

10. Financial

contributions of States Parties to the Preparatory Commission shall be deducted

in an appropriate way from their contributions to the regular budget.

The financing system is complicated by the fact that States can deduct from their assessment the value of in-kind contributions. The Treaty states:

22. The

agreements or, if appropriate, arrangements concluded with States Parties or

States hosting or otherwise taking responsibility for facilities of the

International Monitoring System shall contain provisions for meeting these

costs. Such provisions may include modalities whereby a State Party meets any

of the costs referred to in hosts or for which it is responsible, and is

compensated by an appropriate reduction in its assessed financial contribution

to the Organization. Such a reduction shall not exceed 50 per cent of the

annual assessed financial contribution of a State Party, but may be spread over

successive years. …

In other words, to the extent that the construction of the necessary facilities is done by a State party, this is considered to be part of their contribution. A number of States, including the United States, have already done so.

The dilemma for the PTS is that, until the Treaty comes into force, the contribution of Signatory States is not really a legal obligation. In this sense, the fact that, as the Executive Secretary reported in August, over 90 percent of the assessments had been paid reflects as general satisfaction of those States with the progress being made. However, this could be put at risk by political changes. For example, when the United States Senate rejected ratification, some of its staff members argued that the United States should cease paying into the PTS. While this was not pursued, at least partly because the Clinton Administration was a proponent of the Treaty, it might be taken up again should an incoming Bush administration become influenced by the anti-Treaty forces.

Over the longer-run, the Treaty contains an interesting provision. It states that

21. The Organization shall also meet the cost of provision to each State Party of its requested selection from the standard range of International Data Centre reporting products and services, as specified in Part I, Section F of the Protocol. The cost of preparation and transmission of any additional data or products shall be met by the requesting State Party.

In other words, beyond the “free” services provided to States Party under the terms of the Treaty, mostly relating to verification, the Organization will be able to charge user fees for additional products. This may become increasingly important in the future. The Monitoring System is not expected to detect many explosions of nuclear weapons, because this is not expected to occur. The complex of stations constitutes a remarkable resource for geophysical research and its operation, as a significant byproduct, will produce data that can be used for that purpose. To the extent that a market for these products grows, the Organization may, over the longer term, become partially self-financing. If so, it will join a small but growing number of international organizations that are allowed to charge “user fees” for some of their services.

Once the treaty comes into force, the CTBTO will become a permanent entity. Yet, it will be in the testing during the preparatory period that the management bases will be set. They will determine how well it can be expected that the permanent functions can be performed. The evidence to date suggests that the organization is able to create and establish its verification system in a cost-effective manner. What will remain to be shown is that, once the Treaty enters into force, that it can maintain the system, respond to the demands of the Treaty and, as the organization matures, develop additional products that can help justify the expense of maintaining “the global burglar alarm”.

Whether it is successful will, in turn, depend on how the organization develops its human resource management and means of ensuring financial viability. It will also depend on whether it is able to integrate its work and experience with the other organizations charged with verification of the elimination of weapons of mass destruction.

Clearly more work must be done on several of these issues. But it can be clearly concluded that the management of the Organization is such that the international community can have confidence in the ability of the CTBTO to perform its functions, and more.

[1] The author has facilitated two annual management retreats of the PTS and has held extensive discussions with senior managers in that context. This paper reflects the author’s views alone and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Provisional Technical Secretariat.

[2] http://www.senate.gov/~warner/ctbt.htm

[3] http://www.ctbto.org/ctbto/summary.shtml

[4] Report of the Executive Secretary to the Twelfth Session of the Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBT/PC-12/1/Annex III), para 2

[5] Ibid., para. 41.

[6] Ibid., para. 21.

[7] CTBT/PC-12/1/Annex IV, para. 36.